Rheanna-Marie Hall interviews travel writer, photographer, and film maker Nick Danziger, to talk about his decade-long project and new book Another Life.

“I have just one more question…” I say, for what must be the twentieth time. I’m talking to Nick Danziger – photographer, travel writer, film maker – and each time I begin to bring the interview to a close, I inevitably start it up again with another question. The more he says, the more I want to know.

Nick Danziger is a world-renowned photojournalist, with numerous awards to his name and whose work has been exhibited across the globe. I’ve called Nick to talk about his newest project, a project which incidentally is also the product of twelve year’s work. So, not that new at all then?

In 2000, the United Nations created the Millennium Declaration, an agenda formed of eight development goals including the eradication of extreme poverty and hunger, a reduction in child mortality, the promotion of gender equality and empowerment of women, and combatting HIV/AIDS, Malaria, and other diseases. In 2005 Nick was commissioned by World Vision to investigate the impact of the Millennium Development Goals. He travelled to eight of the world’s poorest countries to document what life was like for the women and children living there. Five years later, and again five years after that, he returned and after spending “over a decade photographing the same people,” the concept of Another Life was born.

Nick describes the book, a collection of all the photographs he took on his visits, with accompanying text by esteemed travel writer Rory MacLean, as a “project that goes very much beyond statistics”.

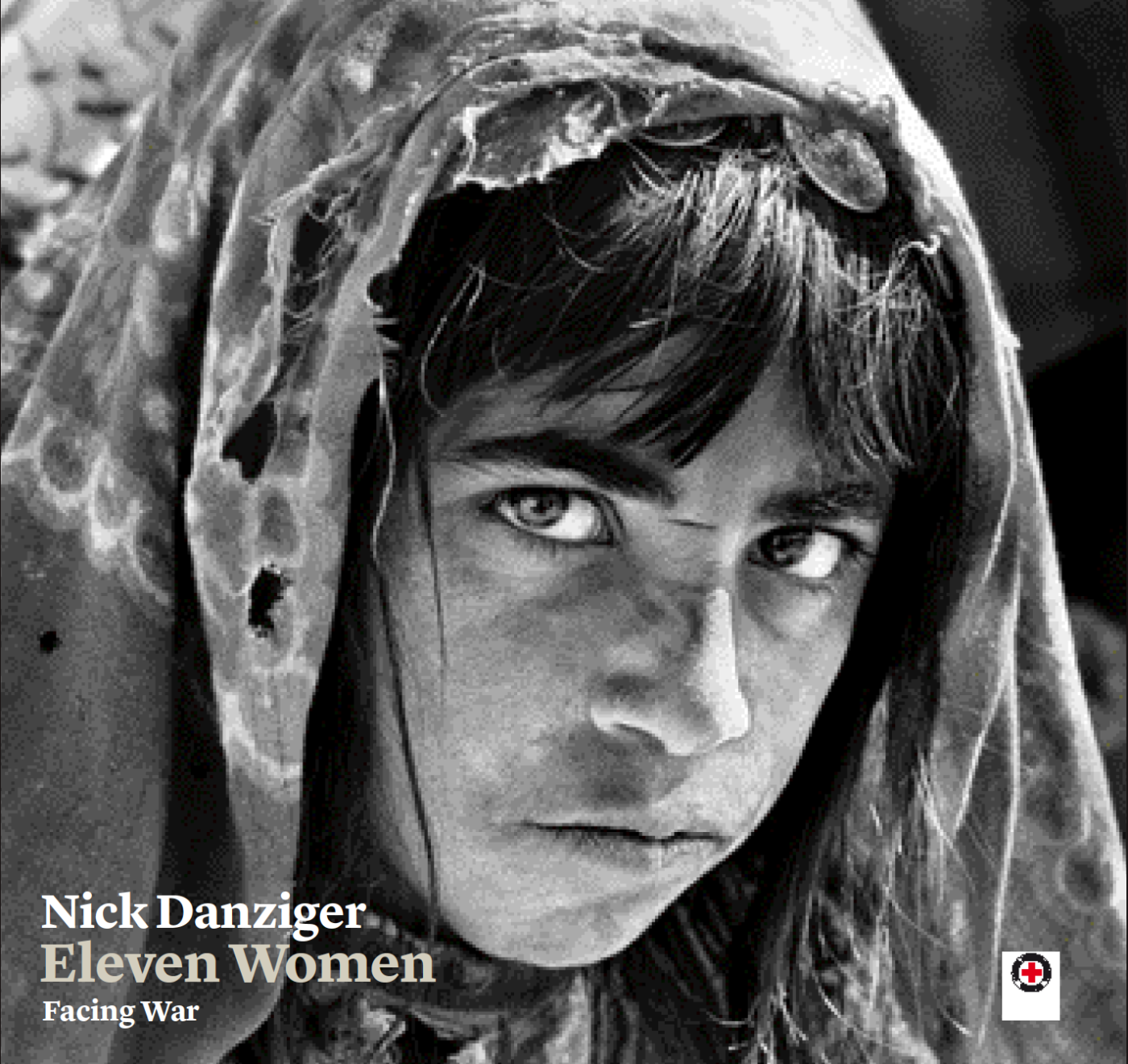

“This will be a photographic book of everyone’s stories,” he tells me. “Many of the issues are related to families, women and children.” The girl on the cover, Aissha, is one of those children, and one who Nick has thus far successfully been able to retrace. “I’ve been following her since she was a baby, [in the book] you’ll see her growing up.”

Nick’s desire to follow their lives is not an easy one. Finding people again after five years will always have its difficulties. In countries where villages can lie hundreds of miles away from the nearest city and some don’t exist on maps, it becomes a mammoth task.

Nick uses Aissha as an example of how challenging it can be to retrace individuals. “Aissha is very difficult to find, she’s a nomad. She spends her time with the family livestock,” he explains. “She’s nowhere near the capital.”

Nick’s original commission was in 2005, but his desire to return and retrace the people he met means that, despite the difficulties, ‘everyone has been revisited a minimum of three times’, and some ‘up to five times’ depending on the circumstances. If he is in already in a country for an exhibition, for example, Nick tells me he’ll use the opportunity to see the people living there again.

Without the support and research of others though, Nick doubts he would have been able to continue with the project at all. “Some of these people are really hard to get to.”

“This works thanks to enormous teamwork,” he assures me. “I could not have done this without the help of numerous people.”

12 year old Aissha, a Fula shepherdess in Niger (2015). Photograph: Nick Danziger

In retracing the lives of people that, originally, were part of a commission for a one-off project, Another Life is a unique concept that goes beyond a brief. Photography is so often a single glimpse into an individual’s life, caught – whether accidentally or intentionally – through the lens. It is this aspect of Another Life that Nick feels particularly strongly about.

“I think it’s really important to have a follow-up,” he tells me. “Personally I think it’s really unusual. You never know what happens afterwards, and a lot of my work is going back.” He explains that returning has been crucial, not only because of “greater perspective” on their lives, but also the “trust that builds up” between Nick and those he photographs. “It’s more than just a project, it’s a life’s work,” he finishes.

I ask if amongst all the people he has met and all the lives he has documented, whether there are any that particularly stand out. There’s a silence while he thinks. “The things that tend to stick are ones about young people because they still have their lives ahead of them, particularly young girls who face numerous barriers and obstacles they wouldn’t face elsewhere.”

The book itself is currently awaiting a release date. It is being hosted on Unbound, a crowdfunding site created specifically for publishing. Crowdfunding, for anyone not in the know, works by way of donations from members of the public. An amount of money is pledged towards the publishing of the book in return for rewards, which range anywhere from a signed copy to dinner with Nick and Rory. Only if the target amount is reached will money be taken, so return on investment is guaranteed.

As he is already a published author with a well-known name and a reputation built over three decades of experience, I’m curious as to why Nick has chosen crowdfunding as a means of publishing. I’m surprised by his answer: even for a seasoned professional, it seems, “it’s really difficult to raise the funding for these types of projects”.

With the current crises across the world, including that of the struggle in Syria from which extraordinary civilian journalism has emerged on social media, I had assumed that humanitarian journalism was on the rise, that the demand was an ever-growing thing. Not so. In fact, the exact opposite.

“It’s definitely getting harder.” He pauses. “Websites want this but websites have insatiable appetites.” He points out that its “celebrity” everyone wants photos of nowadays; just look at magazines. And he’s right. I write this with a glossy magazine in my bag at this moment, adorned with a famous face. And inside is much the same. Beautiful faces. Lives ever on the up. Save for one article dedicated every issue to ‘problems’ it’s designed for escapism. Which I unashamedly admit to wanting. But now it’s pointed out to me, the gap for humanitarian journalism is glaring. And even when it is featured, Nick tells me it’s a battle for good coverage: “It’s harder to get published in traditional outlets, and even then, not in the forefront.”

Nick admits that he is at an advantage compared to new photojournalists looking for this kind of career. “It’s possible to place this work if you have a name,” he explains. “I’ve been very fortunate. I’m likely to get published. But then again, I think it’s unfair, if you have a name… People know who you are. It’s harder if you’re an unknown.” It is no longer enough to have good material. The name that comes with it, in this case Nick Danziger, provides reassurance to publishers that it will sell and readers that it is reputable.

“I have just one more question…” I begin, and I mean it this time. Why, I ask, after all he has told me about the demands and desires of the industry and the mainstream media, has he chosen to pursue humanitarian journalism so determinedly for so many years.

“We’re not hearing these types of stories,” he tells me. “Our world is so unbalanced.”

“It’s important we do have an understanding […] They are remarkable people, heroic. Everyday life is a challenge for them.”

Nick pauses a moment before he continues.

“They’re always in my head. It’s one of the reasons I return; I know they’re still out there.”

Another Life: one commission turned into a life’s work.